The AI Republic of Letters

Reflections on a fragile world

Please forgive a brief digression from policy talk. I hope these reflections are of use.

Quick Hits

If you are in DC, please consider joining the AI Bloomers happy hour with me and Brian Chau of Alliance for the Future next week: Wednesday, May 15, 6pm at Union Pub. Please use the link to RSVP. It would be great to meet you.

I had a piece in Tech Policy Press on what the TikTok ban says about the fundamental contradictions in US tech policy, and more broadly, how we have little idea how to govern the internet. I also appeared on Nathan Labenz’s The Cognitive Revolution to discuss California’s SB 1047 with Nathan Calvin and Steve Newman; this was a fun discussion.

AlphaFold 3 came out, with the ability to predict the biomolecular structure of “all of life’s molecules”—proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands—and the interactions between them. Particularly interesting is the use of diffusion models, which are inspired by the same physics that occur when you pour milk into a cup of coffee. Imagine “pouring” the sequence of a biomolecule into a computational cup of water; the mixture that eventually emerges from the two is the predicted structure. This is a highly stylized description, but it’s not entirely wrong.

The Main Idea

I want to tell you about two portraits.

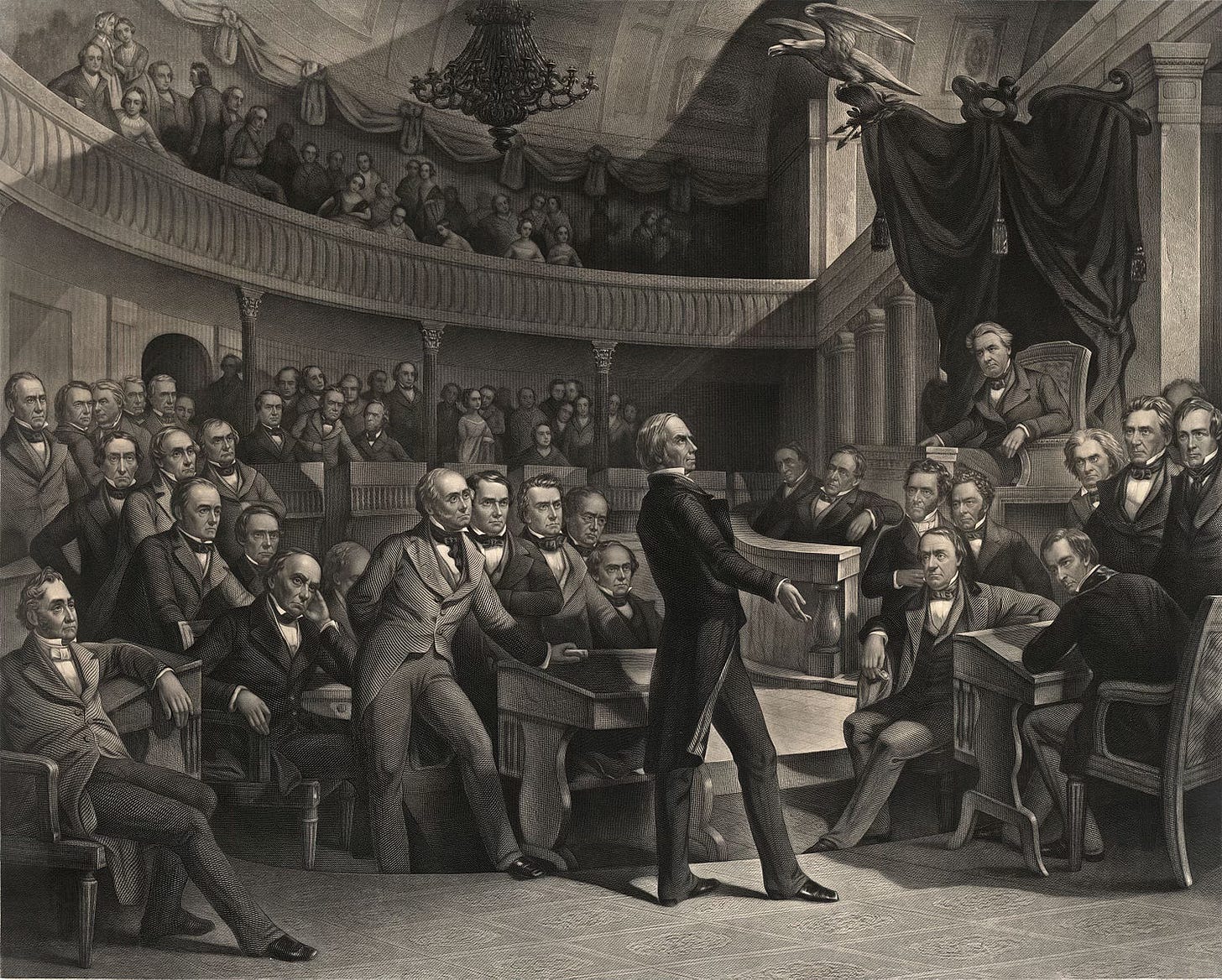

One is a 19th century lithograph of Henry Clay speaking on the Senate floor; it hangs in the hall outside my bedroom. To Clay’s left is Daniel Webster, the fiery Northern statesman; to his right is John C. Calhoun, the personification of the Old South. Clay is in the middle, literally and, of course, figuratively. Clay was known as the “Great Compromiser,” working as he did to forge a middle path in the conflict over slavery. He spent his life trying, and ultimately failing, to peacefully resolve fundamental tensions in our Constitution and our republic.

Clay also articulated a vision for how America could thrive as the First Industrial Revolution took hold: his “American System” was a vision for how our young (then, and still) commercial republic could thrive during a period of unprecedented technological transformation.

The other portrait, of Ludwig van Beethoven, hangs over my desk. Even when I leave my home office, I often feel him hanging over me. Beethoven’s work served as a bridge between the classical and romantic eras of music. He used the classical form to invent musical romanticism. By fusing the two, he created a kind of music that no one, not even the romantic composers who came after him, could ever duplicate.

While Beethoven’s music on the surface is about titanic conflict, at a deeper level, it is about unity, about the puzzling interconnectedness of things that appear to be opposites. He collided different harmonies, themes, and rhythmic structures together, as if to find the building blocks of music itself—and perhaps, to convey an underlying compositional unity between emotions and ideas that superficially seem distinct. Beethoven was, I sometimes joke, the first particle physicist.

As he struggled with the onset of hearing loss, in his early 30s, Beethoven contemplated suicide. Ultimately, however, he chose to continue his artistic pursuits, and his fusionist project began in earnest. “From today on,” he subsequently wrote, “I shall take a new path.”

I suspect that all of us, eventually, will be forging new paths—whether we wish to do so or not. No technological transformation has happened as quickly as the one that I believe will happen over the next 10-20 years. As I forge my own new path, Beethoven and Clay alike will be on my mind.

Over the past few weeks, one of the first major policy struggles over AI has emerged: California’s SB 1047. I have strong priors on this bill, and I was one of the first people to critique it forcefully. But that’s not my point here. Instead, I want to reflect very briefly on what I’ve seen and learned as a small participant in that debate, and how Beethoven and Clay have helped me navigate it.

In college, I was the target of death threats for critiquing an earlier version of what we would now call “woke” policies promulgated by my school’s administration. I’ve received threatening voicemails from politically connected organizations for being part of efforts to make New York City’s public transportation more efficient. I’ve known colleagues who have been through much worse.

I am here to tell you that the current debate over AI, no matter its flaws (and there are many), is among the most elevated and nuanced I have seen during my career in public policy. I am here to tell you that my intellectual “opponents”—those who worry immensely about AI catastrophic risks—are, by and large, honest and good faith people. I believe they are wrong, that they are sometimes anti-empirical, and that their proposed policies could be ruinous, but that is beside the point.

Are there grifters? Without a doubt—on all sides of this debate. Are there cynical actors? You bet. Yet by and large, I’ve never had more worthy intellectual allies or opponents. We write our Substacks and record long podcasts with our philosophical musings and our theories—sometimes overwrought, sometimes pretentious, but almost always well-meaning. Essays in the original French sense of the term—essayer, “to try.”

It’s nice, this little republic of letters we have built. I do not know how much longer it will last.

As the economic stakes become greater, I suspect the intellectual tenor of this debate will diminish. Policy itself will push in this direction, too, because government has a tendency to coarsen everything it touches. So today, I only want to express my appreciation, to my friends and opponents alike. I will enjoy our cordial debates for as long as we can have them.

Like Clay and his contemporaries, I believe we are standing before a tsunami. Like them, we are trying to resolve fundamental tensions in the architecture of free society. We do not know how to govern the internet. We do not know how statecraft might be transformed by AI. What happens as biology becomes an information science, and hence a form of statistics, and hence—speech?

We have little more than the wisdom of history and our own experience to guide us: This, to me, suggests that the virtues of the Enlightenment are, at the very least, our best starting point for grappling with what is to come. Like Beethoven, I believe a fusion of the classical and the new is what we require. Unlike Beethoven, I do not believe I can craft that fusion alone. I hope, and I believe, that we will do it together.

Every day, I try remember how little I understand, even—especially—as the debates get more heated. I try, and usually fail, to grasp the magnitude of what is happening all around us. Most of all, though, I try to listen—attention, after all, is all you need.

Great article! Makes me want to apologise to you for any comments that might have been rude to you on Twitter or here.